In 1996, this off-grid house designed by architect Martin Liefhebber was one of two concept homes selected by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation(CMHC)as part of their Healthy Housing Design Competition.

What was to be built was a three-bedroom semi-detached home on a small lot in downtown Toronto, And beyond its intention to have extremely healthy indoor air quality, it would have no connection to the electrical grid, municipal water supply or sewer system. Our review of this house is based on the CMHC’s research report, along with the homeowners’ testimony after more than 20 years living in it.

The ‘Toronto Healthy House’ design concept

As a semi-detached, three-bedroom, 1700 square foot home, in size this is nothing out of the ordinary. But the efforts and strategies put in place for autonomy and reduced resource-consumption during operation made this house a big news maker in its day, even earning it a spot on a Canadian postage stamp.

It was innovative but not alone; the 90s was a time of low-tech and high-performance housing improvements, such as: low-flow faucets, highly-insulated and airtight building envelopes, passive heating design and the use of thermal mass to balance interior temperatures. When well-organized and thoughtfully executed, such components can lead to significantly reduced resource consumption during the operation of a home.

The stated performance goals of the Toronto Healthy House were as follows:

- It should consume a maximum of 120 liters of water a day, which is one-tenth of a normal dwelling (rain and snow are the only sources of water).

- 75% of the total energy would be provided by the sun (passive heating and photovoltaic power generation).

- The remaining 25% of required energy would be provided via a gasoline-powered generator.

Collecting and purifying rainwater

The most crucial prerequisite to designing a successful autonomous home water system is to reduce consumption. For example, this house includes a toilet that consumes only 6 liters per flush, which wasn’t mandatory until 2014.

水的重复利用也很重要——洗衣机、淋浴器、浴缸和浴室水槽的废水被回收和净化,用于厕所。由于没有市政连接,唯一的水源来自雨水和融雪;它被回收并储存在一个20000升的混凝土罐中,埋在房子的后院。In addition to mechanical filtration systems (coarse, sand and activated carbon filters), water passes through aWaterloo Biofilter.

The system is designed to treat 600 litres of rainwater per day, which is done without using any chemicals. Water is first filtered by charcoal, purified with ultraviolet light, then stored in the underground tank, which is covered with a layer of limestone to neutralize acid rain.

All the water collected will see between 3 and 5 separate uses, including exterior irrigation, before finally being discarded into theclass 6 septic system, equipped with a sand filter to purify wastewater.

Solar energy collection

A successful strategy to power a home with solar energy begins like the water system, with the core principle of first reducing demand. To that end, the appliances and systems of this house were designed and chosen for their reduced operational demand of energy.

On the roof are eight photovoltaic solar panels that can generate 2.3 kW of electricity on sunny days, which should provide the bulk of the house's electricity consumption. Enough power to meet the total electrical demand during 4 days without sunshine is stored in direct current (DC) lead batteries.

The high-efficiency converter (which transforms the direct current from the 48-volt battery into 120-volt domestic alternating current) can withstand a strong power surge without being damaged and consumes very little current when left idle.

A gasoline generator provides an additional 900 kWh, which amounts to approximately 25% of the total demand. The annual cost of occupying the house was originally pegged at about $300 at current values.

A healthy home

虽然它的自主性是这座多伦多住宅最受关注和赞誉的地方,但CMHC倡议的主要任务是展示建筑技术,为居住者确保更安全的室内空气质量。

To meet those stated goals, ventilation air is controlled at the source by a continuously operating energy recovery ventilation system (ERV) that filters pollutants.

All building materials were carefully selected to prevent any interior source of chemical and biological contaminants by using products such as concrete and glass countertops and water-based finishes that are low in volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

Reflections of the owners 20 years later

Rolf and Diana Paloheimo, along with their two children, have lived in this revolutionary house for almost 20 years now. During aninterview with the Globe and Mail, they were asked for their reflections after all these years and mentioned the following:

"We didn't expect to like the passive solar energy that comes through the south-facing windows as much as we do. It lights up the house quite a bit in the winter and together with the radiant-floor heating, the house is much cozier than we expected," Mr. Paloheimo says. (The house also has an electric, forced-air furnace.)

Ms. Paloheimo says: “I didn't like the house at first because it was complicated, but I have grown to love it, especially the coziness and warmth on cold days. I also like it structurally and architecturally, with its little balconies and other features."

Alterations and additions made over the years

The family found that the inclusion of a ‘drying closet’ (a small room with circulated air) instead of a dryer did not meet their laundry needs, particularly while raising two small children, and eventually installed a clothes dryer.

The original refrigerator was built by Mr. Paloheimo himself, with an exterior compressor. The idea was nothing short of brilliant, with hopes that the cold exterior air would provide cooling in winter and, in the summer time, heat extracted from the refrigerator would be jettisoned to the outdoors to keep the home cooler. It did work to some degree but not perfectly, so eventually they switched to a conventional highly-efficient fridge. All homeowners should also learn toorganize their fridges to reduce food waste with our useful guide here.

Paloheimo spoke of it in aninterview with the Toronto Star: “the fridge worked fine most of the time, but the freezer never worked in the summer. We couldn’t have ice cream when we really wanted it. So we got rid of that and bought a high-efficiency fridge from Europe.”

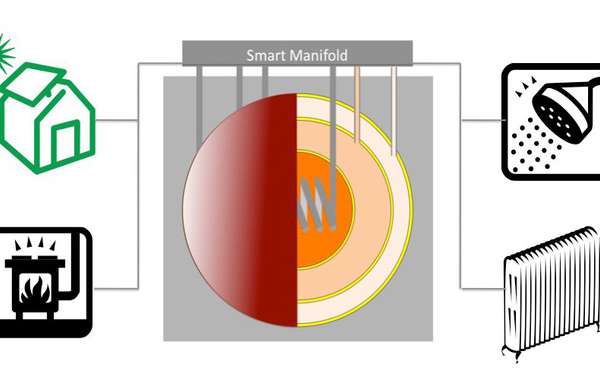

The house was not originally equipped with air-conditioning, but the family found that closing shutters and curtains still didn’t provide enough respite from the heat, so they connected to the electrical grid after a few years and installed an air-to-water heat pump that provides air-conditioning in summer and a portion of heat in winter, which reduces the demand on the gasoline-powered generator. Part of the energy captured by the solar panels is now resold through the power grid.

Water management proved to be more problematic than anticipated and the family had to make adjustments in the early years. "In the beginning, we ran out of water a few times and had to fill our tank with the pipe from a neighbor's house. But now, we usually have too much water. And washing the dishes with rainwater is really very effective. "

Cost of living

就总运营成本而言,最初的预测似乎有点过于乐观。然而,即使是每年大约1000美元的运营成本(超过估计的三倍),它仍然代表着比相同大小的传统房屋减少了三分之二。

Off-grid living in the city - does it make sense?

Houses built on land that does not have access to municipal services such as water, sewage and power, will likely require considerable investment to provide these amenities in a decentralized manner. However, that can still be a lot cheaper than the cost of bringing municipal services such as water lines and hydro poles for example, from a distant hookup. In such remote locations, there is often no option but to go it alone.

But in the heart of an urban core such as downtown Toronto, we find it difficult to justify constructing entirely independent systems, particularly in terms of their environmental impact. In an urban neighbourhood you have easy access to existing service networks, which is the most economical option in every respect, particularly in terms of maintenance and repair.

Words of advice offered in hindsight from one of theoriginal designers of the 1977 Saskatchewan House激发了全球被动屋运动的灵感,这似乎总是正确的——“被动比主动好,简单比复杂好,运动部件会失效”。

像多伦多健康之家这样的自治建筑,触动了设计师和业主的想象力,毫无疑问地推动了行业向可持续建筑实践的发展。但是现在我们所使用的生命周期分析工具表明,这个项目所要展示的减少环境影响的目标根本没有达到。

For one, the lifecycle of the batteries that are necessary for the storage of energy represent an embodied ecological cost that is not often considered (althoughbattery technology has greatly advancedsince then).

Further to that, while we offer full kudos for the collection and use of rainwater, the concrete tank along with the required network of pipes and filters to render water potable represents increased resource consumption, complication and cost compared to the more simplistic approach involving water conservation, collecting rain in a barrel for your garden, and hooking up to the city water main and sewers right in front of the house.

The addition of a gas generator to power the home is the part we have the hardest time with. In a case like this, it can be argued that if you want to know if something is a good or bad idea, simply multiply it by a thousand. Now, imagine the noise and air pollution in a neighbourhood where each of a thousand homes runs a gasoline generator to provide ¼ of their required power.

Resilient home design and survivability

一些房主从共享资源中寻求自主权,作为一种方式,以确保他们的房屋在电网故障时的生存能力;这是一个基于生活方式和个人安全的决定,其优点不容置疑。然而,对于那些试图限制它们对自然世界的影响的人来说,这不是一个好办法。共享的水、污水和电力网络更便宜,对生态的影响也最低。

也就是说,我们要向所有让这个家成为现实的人致敬。没有改进和修改,原型和创新想法很少能经受住时间的考验,它们也不应该这样做。他们的价值在于激励别人捡起球,带着球奔跑。

Many CMHC educational materials have come from the research that was done though the life of the Toronto Healthy House, which was far ahead of its time. And more people are now aware of the abundance of rainwater than can be harnessed, along with passive and active solar energy collection. We offer this critique secondary to the congratulations we offer the designers and homeowners for executing a noble vision of sustainable housing.

Remember having seen that project in a CMHC flyer at the time I was beginning my bachelor in architecture. Very happy to have such an update 20 years later. Good job!

"In an urban neighbourhood you have easy access to existing service networks, which is the most economical option in every respect, particularly in terms of maintenance and repair."

What are those maintenance and repair costs of this house's services, yearly? Exact numbers, please.

I don't quite understand the question sorry, or who it's addressed to - are you asking Ecohome or the homeowners? We don't have any costs for maintenance of this house, is that what you're looking for? The inclusion of the quote makes me think you may not be asking that, and as for costs for hooking up to municipal services it would be very difficult for us to provide you with exact numbers. If you can be more specific in what you're looking for I'll see what we can find.